The moment I truly understood tokenization was not when I read about it in a textbook, but when I watched a production NLP pipeline fail catastrophically because of an edge case the tokenizer could not handle. After two decades of building enterprise systems, I have learned that tokenization—the seemingly simple act of breaking text into smaller units—is the foundation upon which all modern language understanding rests. Get it wrong, and everything downstream suffers.

Understanding Tokenization at Its Core

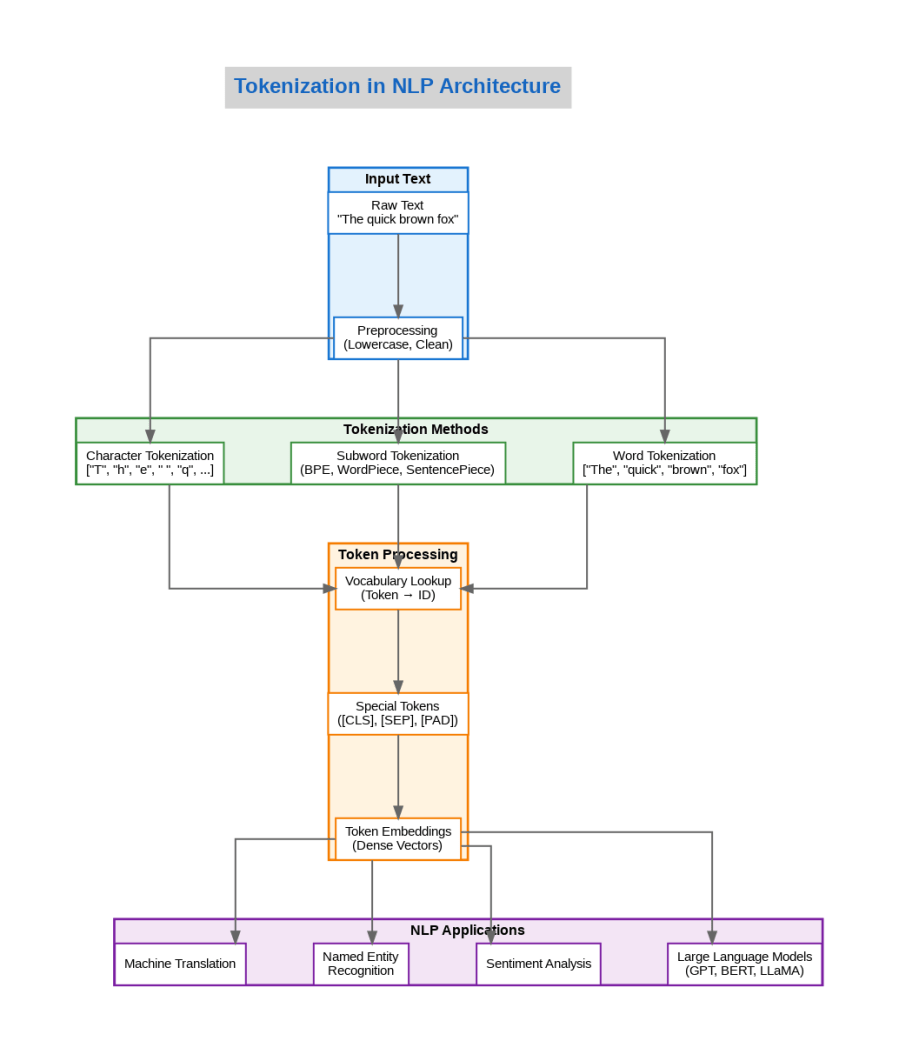

Tokenization transforms raw text into discrete units that machine learning models can process. While the concept sounds straightforward, the implementation decisions carry profound implications for model performance, vocabulary size, and the ability to handle multilingual content or domain-specific terminology. In production systems I have architected, the choice of tokenization strategy has determined whether a model could generalize to new domains or remained brittle when encountering unfamiliar text patterns.

The fundamental challenge lies in deciding what constitutes a meaningful unit. Word-level tokenization splits text on whitespace and punctuation, producing tokens like “The”, “quick”, “brown”, “fox”. This approach works well for English but struggles with agglutinative languages like Turkish or Finnish, where single words can encode information that requires entire phrases in English. Character-level tokenization solves the vocabulary problem by treating each character as a token, but it forces models to learn spelling patterns from scratch and dramatically increases sequence lengths.

The Subword Revolution

Modern NLP has largely converged on subword tokenization as the optimal compromise between vocabulary size and semantic granularity. Algorithms like Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), WordPiece, and SentencePiece learn to segment text into frequently occurring character sequences, allowing models to represent common words as single tokens while decomposing rare words into recognizable subunits. The word “unbelievable” might become [“un”, “believ”, “able”], preserving morphological structure while keeping the vocabulary manageable.

In transformer-based models like GPT and BERT, the tokenizer is not merely a preprocessing step but an integral part of the model architecture. The vocabulary learned during tokenizer training directly determines the embedding layer dimensions and influences what patterns the model can efficiently represent. I have seen projects fail because teams treated tokenization as an afterthought, training models on one tokenizer and deploying with another, or failing to account for domain-specific terminology that the tokenizer fragmented into meaningless subunits.

Production Considerations

Deploying tokenization in production systems requires attention to several critical factors. First, tokenization must be deterministic—the same input must always produce the same output, regardless of when or where the tokenization occurs. This seems obvious but becomes challenging when dealing with Unicode normalization, whitespace handling, or special characters that different systems represent differently. I have debugged production issues where models produced different outputs simply because the tokenizer received text with different Unicode normalization forms.

Performance matters significantly at scale. Tokenizing millions of documents requires efficient implementations, and the choice between pure Python tokenizers and optimized Rust or C++ implementations can mean the difference between processing jobs that complete in minutes versus hours. The Hugging Face tokenizers library, built on Rust, has become the de facto standard for production deployments precisely because it offers both correctness and speed.

Special tokens deserve particular attention in production systems. Tokens like [CLS], [SEP], [PAD], and [MASK] serve specific purposes in model architectures, and incorrect handling can silently degrade model performance. I have encountered systems where padding tokens were not properly masked during attention computation, causing models to attend to meaningless padding and produce degraded outputs.

Tokenization Across Domains

Different domains present unique tokenization challenges. Medical text contains terminology like “acetylsalicylic acid” that general-purpose tokenizers fragment into meaningless subunits. Legal documents use precise phrases where tokenization boundaries can alter meaning. Code requires tokenizers that understand programming language syntax rather than natural language patterns. In each case, the decision to use a domain-specific tokenizer versus fine-tuning a general-purpose one involves tradeoffs between specialization and transferability.

Multilingual tokenization adds another layer of complexity. A tokenizer trained primarily on English text may allocate disproportionate vocabulary space to English subwords, forcing other languages into longer token sequences that consume model context and degrade performance. Production systems serving global audiences must carefully evaluate tokenizer coverage across target languages and potentially employ language-specific tokenization strategies.

The Path Forward

Tokenization continues to evolve as researchers explore alternatives to fixed vocabularies. Byte-level models that operate directly on UTF-8 bytes eliminate the need for explicit tokenization but require architectural changes to handle the resulting longer sequences efficiently. Character-aware models combine the benefits of subword tokenization with explicit character-level representations, improving handling of rare words and morphological patterns.

For practitioners building production NLP systems, the key insight is that tokenization is not a solved problem to be ignored but a critical design decision that shapes model capabilities. Understanding how your tokenizer handles edge cases, domain-specific terminology, and multilingual content is essential for building robust systems. The tokenizer is the first component that touches your data, and its decisions propagate through every subsequent processing step. Treat it with the attention it deserves.

Discover more from C4: Container, Code, Cloud & Context

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.